The Anthropocene seems to have a paradoxical relationship with knowledge.

On the one hand, it’s often describedE.g. in Lewis & Maslin (2018) and Harari

(2015).

as the result of a centuries-long exponential

growth of knowledge fuelled by investment: The interlocking

feedback loops of capitalism and science – “the investment of profits to

generate more profits, and the production of ever-greater knowledge from

the scientific method”Lewis & Maslin (2018), 14

– have acted as “history’s chief engine for the past 500

years”Harari (2014), 306

and made “Homo sapiens […] a geological superpower”Lewis & Maslin (2018), 5

.

On the other hand, the Anthropocene is also seen as the result of a

centuries-long lack of knowledge – the work of “a ‘humanity’

deficient in knowledge”Bonneuil & Fressoz (2016), 65

that unwittingly set “Earth on a new path in its long

development”Lewis & Maslin (2018), 5

, characterised by climate and ecosystem breakdown.

Climate scientists express this widespread view when they claim that

“[w]e are the first generation with the knowledge of how our activities

influence the Earth system”.Steffen et al. (2011), 757

Taken together, these narratives paint the picture of a

civilisationThe globally integrated complex system that encompasses

most of today’s societies, economies, cities and smaller social systems

and their economic, political, military, diplomatic, social and cultural

interactions.

that is in crisis because it was at the same time smart

enough to exponentially increase its impact on the planet and too stupid

to understand the consequences of that.Until recently, this has been more or less my own view;

see the first section of my “Complexity, Metaphor and

Radical Change”.

But this picture is misleading and dangerous. It wrongly models collective knowledge on a specific conception of of individual knowledge, distorts historical facts, obscures the true causal structure of our situation, and makes effective action in the face of our existential crisis less likely. Clearing up this misunderstanding will help us understand what really brought us into our current predicament – and how we can take steps beyond it.

Varieties of knowledge

So, what is knowledge?

Let’s start with our pre-philosophical, everyday understanding of it. The Oxford Dictionary of English begins its definition as follows: knowledge is “facts, information, and skills acquired through experience or education”.

There are two different types of knowledge in this definition:

- knowing that – for example, I know that there is a dictionary, and I know that the dictionary defines knowledge in this way (a fact about which I have information);

- knowing how – for example, I know how to use the dictionary to look up this definition (a skill).

The first type is also called propositional knowledge and is the

mainstay of philosophical theories of knowledge. Textbook

introductionsSee, e.g., Pritchard (2010).

usually spend a paragraph describing knowing

how, another paragraph explaining why it’s derivative, and the

remaining pages on knowing that.There are a few notable exceptions, first and foremost

Ryle (1949).

This dominance rests on “the common assumption that reality has a

propositional structure or, at least, that the proposition is the

principal form in which reality becomes understandable to the human

mind”.Zagzebski (1999)

Research into human perception and cognition suggests that this

assumption is wrong.This argument has been made early on by Craik (1943),

who states that thought’s “essential feature is not […] propositions but

symbolism, and that this symbolism is largely of the same kind as that

which is familiar to us in mechanical devices which aid thought and

calculation.” Of course such a position has to be naturalistic,

i.e. understand these questions as empirical ones.

On the most fundamental level, our brain makes sense of

the world using generative or predictive models.For summaries of the research on predictive processing

see e.g. Clark (2013) and Seth (2021).

Reality is just a causal constraint on these models.

Explicit and Implicit Models

A generative model

aims to capture the statistical structure of some set of observed inputs by tracking […] the causal matrix responsible for that very structure. A good generative model for vision would thus seek to capture the ways in which observed lower-level visual responses are generated by an interacting web of causes – for example, the various aspects of a visually presented scene.Clark (2013), 2

In other words, a generative model predicts the causes for what we perceive.

This can happen on multiple levelsSee Ramstead et al. (2019) for “a multiscale ontology

of cognitive systems“, i.e. a framework for integrating accounts of

systems on these different levels.

, from individual perception to scientific explanation:

our brain tries to figure out (predicts) the objects and movements that

cause our visual perception; a scientific model tries to figure out

(predicts) the systems and processes, entities and laws that cause

experimental observations.

From this perspective, a third type of knowledge appears to be more fundamental than the two we’ve encountered so far: knowledge of, or what the dictionary describes as “the theoretical or practical understanding of a subject”. We can now define this understanding more technically as having access to a generative model of a subject.

We get from knowledge of to knowledge that if we

“think of models as entailing propositions”Bailer-Jones (2009), 186

: They are predictions about how our environment will

behave, derived from explicit models. Explicit models are

consciously articulated, interpretive descriptions of our environment,

and we pay active attention to them in order to use them.

Knowing how is based on models, too – implicit

models, in this case: non-conceptual, embodied representations of

our environment that we use unconsciously. Implicit models are at the

heart of every skill; their embodiment can consist in practices, habits,

instincts, and all other parts of our phenotype, from basic body

structure to hairstyles, from language to calluses.In this respect, it corresponds to what Polanyi (1966)

called tacit knowledge. Holland (1995, 33) takes up this label

to “distinguish two kinds of internal models, tacit and

overt. A tacit internal model simply prescribes a current

action, under an implicit prediction of some desired future state, as in

the case of the bacterium. An overt internal model is used as a basis

for explicit, but internal, explorations of alternatives, a process

often called lookahead.” This distinction is co-extensive to the one

made here.

In other words, “an agent does not have a model of its world

– it is a model”. Friston,(2013), 213 (my emphasis)

Take a fish as an example: its body “can be considered to

be an implicit model of the fluid dynamics and other affordances of its

watery environment.”Seth (2015), 6

If we think about models in this way, it becomes clear that every

system is a model of its environment – at least every stable system that

survives in its environment (which is the type of system we’re usually

interested in).ibid., 156

This holds for all scales, from single cells and organisms to,

importantly, social systems:Ramstead et al. (2019).

a team models its organisational environment, a company

models its market situation, a civilisation models the world it

inhabits.

This requires us to rethink what collective knowledge is: It is not the aggregation or collective adoption of individual knowledge, of explicit models available to individual attention and expressed in books, papers, and databases. It is access to explicit and implicit models at the level of the collective – the models social systems have of their environment.

Technology and Techne

Explicit collective models are realised as

technology. We can think of technology as “a programming of

phenomena to our purposes”, a “purposed system”.Arthur (2009). This understanding resonates with

Heidegger’s view of technology as the practice of turning everything

into a means: “Everything approaches us merely as a source of energy or

as something we must organize.” (Blitz 2014)

This gives us a usefully broad scope of the concept,

including entities like “monetary systems, contracts, symphonies, and

legal codes, as well as physical methods and devices”.Arthur (2009)

Technology is combinatorial (technologies are combinations of

existing components) and recursive (these components are themselves

technologies).ibid.

As a result, the models realised in any higher technology

(that combines more basic technologies) cannot be held individually

anymore:

[T]echnology becomes a complex of interactive processes—a complex of captured phenomena— supporting each other, using each other, “conversing” with each other, “calling” each other much as subroutines in computer programs call each other. The “calling” […] is ongoing and continuously interactive.ibid.

It is therefore collective actors (i.e. social systems) who hold the

models: teams, institutions, communities, industries, economies,

civilisations – depending on the recursion level and timeframe under

consideration, and on whether we look at an individual technology or

bodies of technology (from specific domains to technology as a whole).

But all of these technologies “are developed not by a single

practitioner or a small group of these, but by a wide number of

interested parties.”ibid.

So technology is what social systems collectively design, use and pay

attention to, from electricity and electronics to meetings and markets,

to realise their purpose. It thus contains one end of a spectrum of

social practices: “explicitly coordinated behavior that is

rule-governed, intentional, voluntary”.Haslanger (2018), 235

At the other end of this spectrum are

patterns in behavior that are the result of shared cultural schemas or social meanings that have been internalized through socialization and shape […] cognition, affect, and experience.ibid.

Taken together, social meanings – from concepts like nation,

race, and gender to scripts for behaviour in specific social situations

– and “skills for interpretation, interaction and coordination that we

exercise ‘unthinkingly’”ibid., 158

constitute a cultural technēA term coined by Haslanger (2017, 2018, 2019,

2021).

:

a network of social meanings, tools, scripts, schemas, heuristics, principles, and the like, which we draw on in action, and which gives shape to our practices”Haslanger (2017), 155

These are “the sources of our practical orientations, that is, the

social preconditions for thinking and acting”Haslanger (2019), 11

– and, a fortiori, the foundation technology rests upon.

A cultural technē thus realises the implicit model of a social

system: the “part of a system that functions […] to regulate our

interactions in a domain”ibid., 156

.

Just as an individual implicit model emerges from the

interactions of a biological system’s components, a social system’s

collective implicit model emerges from the interactions of its

components, from people and artefacts to ideas and institutions.This conceptualisation of social systems is close to

DeLanda’s Assemblage Theory (DeLanda 2005). I regard the of kinds of

things just named as equally real, but ultimately existing as patterns

in a high-dimensional state space. See my “From Predictive Processing to Topological

Thinking: Prolegomena to a Future Paradigm”.

It is not an achievement of conscious individual action

or an aggregation of individual models, but an emergent property of the

larger system.

We can now map out the varieties of knowledge we have found in the following way:

| Individual | Collective | |

|---|---|---|

| Explicit | Knowing That | Technology |

| Implicit | Knowing How | Cultural Technē |

Types of knowledge

We can use this map to help us understand why our civilisation is in crisis – and to expose what is just a smokescreen explanation for this fact.

Our Failing World Model

Collective knowledge on the civilisational level is our

civilisation’s (explicit and implicit) model of its environment (“the

world”). A model that has been quite useful, judging from humanity’s

evolutionary success in terms of growth, spread, and environmental

transformation.See Lewis & Maslin (2018) for a history of this

impact.

(This is the perspective of the “growth of knowledge

enables the Anthropocene” narrative.)

Of course today we see that it is exactly growth, spread, and

environmental transformation that massively threaten our survival as a

civilisation (and possibly as a species).See Servigne & Stevens (2020) for an

overview.

This suggests that the impact of these phenomena on the

Earth System and thus on our collective future is not tracked in our

civilisation’s model of the world; otherwise it would behave

differently. (This what the “lack of knowledge enables the Anthropocene”

narrative highlights.)

In other words, our model of the world is failing.

The most common hypothesis why it is failing is this: Humans just can’t comprehend complex systems, nonlinear change, and long causal chains because they’re not evolutionary equipped for that – it wasn’t necessary in our original cognitive niche.

This is the standard answer of the frustrated scientist, and the one

I have accepted for a long time.See, e.g., “Complexity, Metaphor and

Radical Change”.

But it is fundamentally flawed: It assumes that our

civilisation’s collective model (the one that is failing)

amounts to the collective adoption of individual models (the

ones that are constrained by our cognitive capacities) – and we have

just seen that this is not the case.

For an illustration, consider the famous “World3 Model”. It describes interactions between world population, industrial growth, food production and limits in ecosystems, and provided the foundation for the influential 1972 Club of Rome report The Limits to Growth. It’s an (explicit) individual model that shows what’s apparently missing from our civilisation’s (implicit) collective one: that we’re part of a giant, growth-producing feedback loop that we have to stop to avoid overshoot and collapse.

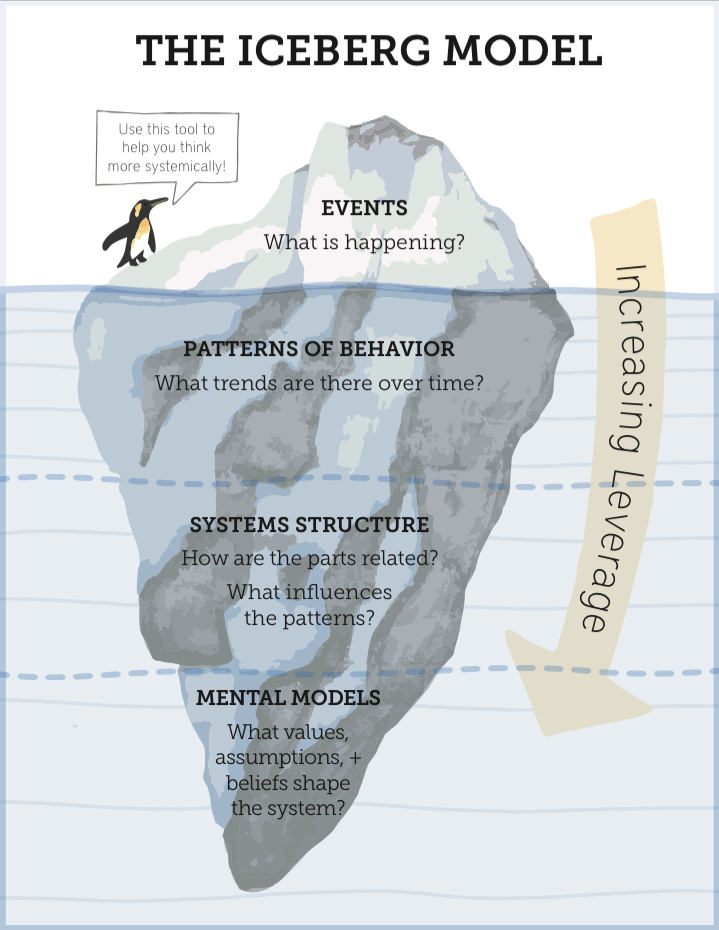

But why has it not been adopted and changed our collective behaviour in the 50 years since its conception, replacing our failing model? That was the explicit goal of Dennis and Donella Meadows and their collaborators when they initially proposed it: to replace an inadequate, reductionist model of the world with a better, holistic one. Donella Meadows describes this strategy in her famous Iceberg Model: the point of greatest leverage to change a system’s behaviour, she contends, is shifting the mental models that shape it.

Talking of mental models in this context points to the heart

of the problem, though: Meadows’s strategy disregards how collective

knowledge is actually realised – a social system’s model is an emergent

result of its components’ interactions, not the collective adoption of

explicit individual models. In effect, she’s trying to replace an

emergent collective model with the collective adoption of an individual

one – which will fail, however much effort one puts into its

promotion.That might be one of the reasons why Meadows changed

her tune slightly in Meadows (1999). There she describes societal

paradigms, “shared social agreements about the nature of reality”

(Meadows 1999, 18), still very much as models that can be made explicit

and changed by influential actors like Copernicus or Einstein. But

beyond that she now recognises a need to transcend paradigms altogether,

which – while still portrayed as an individual activity (ibid. 19) – is

quite close to the therapeutic approach towards ideology described

below.

This brings us back to the question, which we can now put more precisely: Why is our emergent collective model of the world, realised in (social and material) technology and, more fundamentally, our cultural technē, failing?

Ideological Oppression

Quite simply because “a cultural technē can go wrong”Haslanger (2021), 28

: It can become an ideology that distorts and

hides aspects of the world the perception of which would question or

threaten the existing social order.This conception of ideology follows Haslanger (2017,

2018, 2021) and goes back to Althusser and the Marxist understanding of

ideology as false consciousness.

This leads us to an alternative hypothesis about why our

model fails: because it is ideologically captured and

distorted.

Far from being incapable of insight into complex systems, people have

made alarming predictions about the trajectory of our current

civilisation as early as the 18th century. So it was possible to develop

and promote adequate explicit models of our world – but they have been

consistently marginalised by ideological oppression.See Bonneuil & Fressoz (2016).

Ideological oppression is an emergent property of the complex system

that is our civilisation: a product of the dominant incentive system,

and a set of systemic constraints on individual behaviour.See Juarrero (1999) for an account of how constraints

have “downward” causal power.

It is so effective because it is widely invisible – “we

typically embody a practice before we even know we are engaged in

it”.Haslanger (2021), 27

As a mechanism, it works like this: Adhering to and amplifying the dominant ideology promises individual benefits (wealth, power, status) while deviation is threatened with punishment (exclusion, loss of status). This shifts dispositions in ideology’s favour and constrains behaviour in a way that is useful to the wider system, i.e. the civilisation the ideology stabilises, without needing to resort to more dramatic measures like physical violence.

In our case, ideology bends individual behaviour towards

extraction and consumption. A growth- and innovation-based

system like ours uses these strategies in two interlocking feedback

loops:On the first feedback loop, see Harari (2014) and Lewis

& Maslin (2018); on the second, Jackson (2017).

growth enables investment, which increases innovation and

productivity, which enable further growth and reduce the need

for labour, which necessitates growth on pain of economic

collapse. Extraction provides the resources to feed these loops, while

consumption provides the demand to drive them.

And in fact, our civilisation has been so successful evolutionarily,

out-growing and displacing almost all other civilisations, because it is

the most extractive and the most innovative at the

same time: When resources are abundant, the most extractive culture will

be dominant, and innovation has made sure resources stay abundant.I will expand on this argument in a future essay.

Ideology can therefore be described on two levels:

On the level of the system, i.e. our civilisation, extractive and consumerist ideology emerge from this evolutionary process as implicit strategies that constrain the behaviour of institutions, humans and other system components in the service of maximising overall growth and thus dominance.

On the level of interactions between the components, extractive and consumerist ideology are a cultural technē captured and distorted by the interests of institutions, humans and other system components that profit from its current configuration.

These descriptions lead to a very different conclusion than the “we’re just too stupid” argument: We’re not too stupid to keep our civilisation out of crisis, we’re too self-interested and blinded by ideology, in the service of a growth-addicted, extractive wider system that we create and that constrains us. We’re not missing cognitive capabilities, but the space to unfold them without ideological constraints.

What to Do

What we need to win this space is not more individual knowledge, but

the collective knowledge how to disrupt and transform ideology:

social technology to change our cultural technē. Three main

components of this social technology are critical theory, social

movements, and alternative institutions.This is similar how Erik Olin Wright describes the

tasks of emancipatory social science: “elaborating a systematic

diagnosis and critique of the world as it exists; envisioning viable

alternatives; and understanding the obstacles, possibilities, and

dilemmas of transformation” (Wright 2010, 10). Of course the latter two

need to be translated into strategic action.

Critical Theory

Critical theory is situated theory that supports the emancipatory struggle of the (ideologically) oppressed from within a social movement. As part of this endeavour and to help open a thinking space without (or at least less) ideological constraints, it delivers a moral, epistemic and ontological critique of ideology.

Critical theory enables the articulation, discussion and moral

assessment of problematic social relations previously masked by

ideology. It thus helps processes like consciousness

raising produce normative knowledgeHaslanger (2021), 56. Note her clarification on the

status of normative knowledge: “What I say here is compatible with a

robust moral realism, a quietist or deflationary moral realism, moral

constructivism, and some forms of moral anti-realism”.(Haslanger 2017,

165) For my own take on this, see “Is there such

a thing as moral truth?”

, which ideally leads to new or reformed norms around

these relations. Examples are the MeToo movement

and how it changed norms around acceptable male behaviour or, more

fundamental, the emergence of intersectional

feminism and how it reframed questions of social position.

In addition, “changes to the epistemic practices are required in

order to loosen the grip of ideology”Haslanger (2021), 55

. Part of this epistemic critique is emancipatory conceptual

engineering. It tries to wrangle concepts from ideology and give

them more useful meanings, e.g. by “debunk[ing] naturalistic accounts of

race and reveal[ing] race to be socially constructed”Haslanger (2018), 231

.

An ontological critique of ideology defends the reality of social

systems and structures against reductionism and methodological

individualism and provides a toolkit to expose ideological assumptions

and positsFor realist social ontologies see e.g. Haslanger (2019)

and DeLanda (2005). Cf. also my “From

Predictive Processing to Topological Thinking: Prolegomena to a Future

Paradigm”.

. Frameworks like the “implicit model as cultural technē”

one proposed here can bridge the gap between ontological and epistemic

critique.

A prerequisite for the practice of participatory critical theory are spaces where the oppressed can articulate and examine their experiences without the framing of the oppressing system, even in its well-meaning, “supportive” guise. These spaces can only be created by social movements and alternative institutions, which can in turn be supported and legitimised by critical theory.

Examples for critical theory include Sally Haslanger’s conceptual

engineeringHer most influential work in this regard is probably

Haslanger (2000).

, Critical Race TheoryFor an overview see Delgado & Stefancic

(2001).

, Bonneuil & Fressoz’s account of the Anthropocene

discourseBonneuil & Fressoz (2016)

, and Mitchell & Chaudhury’s critique of white

apocalyptic thinkingMitchell & Chaudhury’s (2020)

.

Social Movements

Social movements are concerted efforts by large groups of people to

demand and promote social change. They “intervene in material

conditions”Haslanger (2018), 231

and try to effect the desired change by one or more of

three pathways:

- Direct action to autonomously implement changes and/or force specific actors and systems to change their behaviour

- Mass action to change the environment of actors and systems, i.e. their incentives, e.g. through material disruption or a shift of public opinion

- Symbolic action to create awareness, influence the political agenda and shift the Overton Window of what’s politically acceptable

All three pathways ideally lead to both direct and indirect results: They make harmful or oppressive behaviours and strategies less attractive or even untenable, promote alternatives to these behaviours, and undermine the invisibility and legitimacy of the dominant ideology.

Successful movements connect what people already care about with a larger cause and enable them to experience self-determination in a collective effort. This creates experiences of agency and choice and thus sets the stage for changing social technē via critique and alternative institutions.

Examples of successful social movements include the suffragettes, the Indian independence movement, the Civil Rights movement, Otpor, and the LGBT rights movement.

Alternative Institutions

The third component is “building alternative institutions and

deliberately fostering new forms of social relations that embody

emancipatory ideals”Wright (2010), 324

, thus changing our cultural technē and over time

civilisation itself.

Alternative institutions include People’s Assemblies, Universal Basic Income, mutual aid networks, and complementary, e.g. local or community currencies. They work outside the current system’s consumption/extraction loops and range from small-scale practices for collaborative decision-making to large-scale socio-economic arrangements.

There are three different pathways how such institutions can fundamentally change the current system. Two of them work bottom-up in an either revolutionary or evolutionary way:

first, by altering the conditions for eventual rupture, and second, by gradually expanding the effective scope and depth of their operations so that capitalist constraints cease to impose binding limits.ibid, 328

A third pathway involves “engaging the state, using it to further the

process of emancipatory social empowerment”ibid., 336

in a process of system transformation rather than

replacement.

Our civilisation is a complex system, and we can’t predict the influence alternative institutions will have on it. Therefore either of these approaches needs to start with experiments of limited scope that can be scaled up if successful (which is exactly how proponents of People’s Assemblies and Universal Basic Income are approaching the issue).

All of these approaches also need to take into account that they are competing not only with specific institutions, but through their connections with and embeddedness in other social systems with a whole set of arrangements (a global civilisation) that has successfully displaced almost all alternatives because it is the most extractive and the most innovative at the same time.

Short of global revolution or collapse, alternative institutions will only be successful in such a competition if they can siphon resources from the existing arrangements into experiments and exploit existing institutions to scale the successful ones. They have to extract resources from an extractive system to outcompete its components, which can happen in one of two ways:

They can introduce effective resource constraints (without tipping the global system into collapse) which change the selection criteria for civilisations in favour of more resource-efficient ones; or they can create new sources of abundance, e.g. through regenerative practices, which enable them to outcompete the current regime under the same selection criteria, but with different resources.

For simple thermodynamic reasons, a shift in energy sources or material technologies will not suffice; there needs to be a fundamental change in social technologies and, first and foremost, our cultural technē. In essence, we need to find and adopt non-material sources of abundance:

[O]n today’s evidence, technologizing our way out of this does not look likely. […] [T]he only solution left to us is to change our behavior, radically and globally, on every level. In short, we urgently need to consume less. A lot less. And we need to conserve more. A lot more. Emmott (2013), 184–186

What we therefore need are paradoxical memes: Ideologies and institutions that can, promoted and prefigured by social movements, outcompete extractive counterparts by opposing and reversing extraction.

Emancipatory Social Technology

If all three components – theory, movements, institutions – are working and mutually reinforcing, we have the knowledge we need: a working and resilient social technology to change our cultural technē.

And we can finally start stepping out of the trap that is the Anthropocene.

References

- Arthur, W. B. (2009), The Nature of Technology: What It Is and How It Evolves

- Bailer-Jones, D. M. (2009), Scientific Models in Philosophy of Science

- Blitz, M. (2014), “Understanding Heidegger on Technology”, The New Atlantis 41, 63–80

- Bonneuil, C., Fressoz, J.-B. (2016), The Shock of the Anthropocene: The Earth, History and Us

- Clark, A. (2013), “Whatever next? Predictive brains, situated agents, and the future of cognitive science”, Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 36(3), 181–204

- Conant, R. C., Ashby, W. R. (1970), “Every good regulator of a system must be a model of that system”, Int. J. Systems Sci. 1, 89–97

- Craik, K. J. W. (1943), The Nature of Explanation

- DeLanda, M. (2005), A New Philosophy of Society: Assemblage Theory and Social Complexity

- Delgado, R., Stefancic, J. (2001), Critical Race Theory: An Introduction

- Emmott, S. (2013), Ten Billion

- Friston, K. (2013), “Active inference and free energy”, Behavioral and Brain Sciences 36(3), 212–213

- Harari, Y. (2014), Sapiens

- Haslanger, S. (2000), “Gender and Race: (What) Are They? (What) Do We Want Them To Be?”, Noûs 34(1), 31–55

- ——— (2017), “Culture and Critique”, Aristotelian Society Supplementary Volume xci, 149–173

- ——— (2018), “What is a Social Practice?”, Royal Institute of Philosophy Supplement 82, 231–247

- ——— (2019), “Cognition as a Social Skill”, Australasian Philosophical Review 3(1), 5–25

- ——— (2021), “Political Epistemology and Social Critique”, in: Sobel, D., Vallentyne, P., Wall, S. (eds.), Oxford Studies in Political Philosophy Volume 7, 23–65

- Holland, J. H. (1995), Hidden Order: How Adaptation Builds Complexity

- Jackson, T. (2017), Prosperity without Growth

- Juarrero, A. (1999), Dynamics in Action: Intentional Behavior as a Complex System

- Kirchhoff, A., et al. (2018), “The Markov blankets of life: autonomy, active inference and the free energy principle”, J. R. Soc. Interface 15, 20170792

- Lewis, S. L., Maslin, M. A. (2018), The Human Planet

- Meadows, D. H. (1999), “Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System”, Sustainability Institute

- Mitchell, A., Chaudhury, A. (2020), “Worlding beyond ‘the’ ‘end’ of ‘the world’: white apocalyptic visions and BIPOC futurisms”, International Relations 34(3), 309–332

- Polanyi, M. (1966), The Tacit Dimension

- Pritchard, D. (2010), What is this Thing Called Knowledge?

- Ramstead, M. J. D., et al. (2019): “Multiscale integration: beyond internalism and externalism”, Synthese 198, 41–70

- Ryle, G. (1949), The Concept of Mind

- Servigne, P., Stevens, R. (2020), How Everything Can Collapse

- Seth, A. K. (2015), “The Cybernetic Bayesian Brain: From Interoceptive Inference to Sensorimotor Contingencies”, in: Metzinger & Windt (eds), Open MIND 35(T)

- ——— (2021), Being You: A New Science of Consciousness

- Steffen, W., et al. (2011), “The Anthropocene: From Global Change to Planetary Stewardship”, Ambio 40, 739–761

- Wright, E. O. (2010), Envisioning Real Utopias

- Zagzebski, L. (1999), “What is Knowledge?”, in: Greco, J., Sosa, E., (eds), The Blackwell Guide to Epistemology

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Harley McDonald-Eckersall, Gregor Groß and Phil Harvey for comments on drafts of this essay.