“2001? I watch it every week”, John Lennon reportedly once

said, Steven Spielberg claims to have seen The Shining over 25

times, and as for me, I’ve hardly seen a Kubrick film less than half a

dozen times, most of them more often.This essay was originally written and published in 2007

as a series

of German-language posts on motorhorst.de. I’m reposting it here in

English (and only slightly updated) because I just rediscovered it – and

still kind of like it.

At the same time, rarely has a director been so regularly

slated in the first reviews of his films (the cold, cold Kubrick), only

to be showered with praise a few years and screenings later (the great,

great master).

Why is that? Why do we have to watch Kubrick films so often? And more importantly: Why do we want to?

Prologue

Kubrick films are pure cinema. They are neither representation nor reenactment of an external world, but its exploration through space, shot, montage and narration. Which means: Kubrick films are cinema for the brain, not the heart.

Just as the mature Mozart uses the means of music as a matter of course and with the utmost certainty, making everything non-musical irrelevant, Kubrick creates films that make everything non-filmic irrelevant. But unlike Orson Welles, whose The Trial might be the most cinematic of all films, or Andrei Tarkovsky, who like no other elicits associations and affects through images, Kubrick is not a manic storyteller or a philosopher of emotions. He is an intellectual and a sceptic.

At the same time, he goes beyond the psychographic symbolism of a Bergman around The Seventh Seal or the incessant reflection on the medium of a Godard. Kubrick’s films are, as he himself says, essays on “intellectual problems”, his subject matter “the great themes”: war and peace, freedom and determination, the fate of humanity, love, sex, the human soul. His films explore the relationship between us and the world, between rationality and irrationality, and their perspective on both is always clearly defined – it is that of the enlightenment.

Kubrick tries to put into pictures what cannot be put into words: For Kubrick, cinema is, as it were, a walk-in theory of the world – it’s thinking in images, not in concepts. “What I would really like to do,” he once said, “is to break up the narrative structures of cinema. I would like to create something really unheard of for once.” His achievement and our challenge: Kubrick did just that in the majority of his 13 films.

Space

Classic anecdote: Ronald Reagan takes up his post in the White House. The tour of his future seat of office is coming to an end, but there is one room he has not yet seen, and so he asks where the War Room is.

Whether it’s true or not, the story captures something important: the immense appeal and attractiveness that the spaces in Kubrick’s films exude. The War Room in Dr. Strangelove, the rotating command capsule of the Discovery in 2001, the landscapes in Barry Lyndon, the Overlook Hotel in The Shining – spaces that you can’t get enough of, that you want to enter, to walk through, that have a reality that transcends all illusion.

They owe this reality to a texture and depth of field that was first seen in Jean Renoir’s La Règle du Jeu and that Kubrick pushes as far as no one had before. Take The Shining: The colours, carpets and wallpapers of the Overlook, the constant movement further into the space as we follow Danny on his excursions through the hotel, accompanied by the alternately rumbling and rustling rolling noise of the go kart, the bang of the bouncing tennis ball with which Jack Torrance sounds out the cathedral-like expanse of the lobby, make the hotel almost physically tangible.

At the same time, these spaces are not overwhelming like their

counterparts in Spielberg’s films which suck you into the

adventure.On this, see Kolker (2011) who provides an ideology critique of Spielberg’s strategy of

overwhelming the viewer.

In Kubrick’s films, spaces don’t force you; they attract

and entice, they invite you to marvel at them – and ultimately point

beyond their physical tangibility. They aren’t merely a frame for

action, but its object and author.

Space in Kubrick’s work becomes, in a sense, three-dimensional thought. The War Room is an expression of the Cold War, not its metaphor. In Paths of Glory, trenches and palaces are places, not images, of power and war. The Overlook is the labyrinth in which the inhabitants get lost, not a symbol for this confusion; the place is the evil, not just its stage – it’s literally what possesses Jack and thus drives and determines the story. The space doesn’t symbolise a concept, it embodies it.

And it not only embodies the concept, but also how it is (or isn’t) grasped – it is at the same time thought turned into place and a place of thinking. For Bill Harford in Eyes Wide Shut, the labyrinths of the flat and the city are mirrors of the desires and needs he cannot grasp and control; Hué’s field of urban debris is not the backdrop for the soldiers’ struggle for clarity and direction in Full Metal Jacket, but its cause, object and obstacle – “the terrain of small unit action is really the story of the action”, says Kubrick himself.

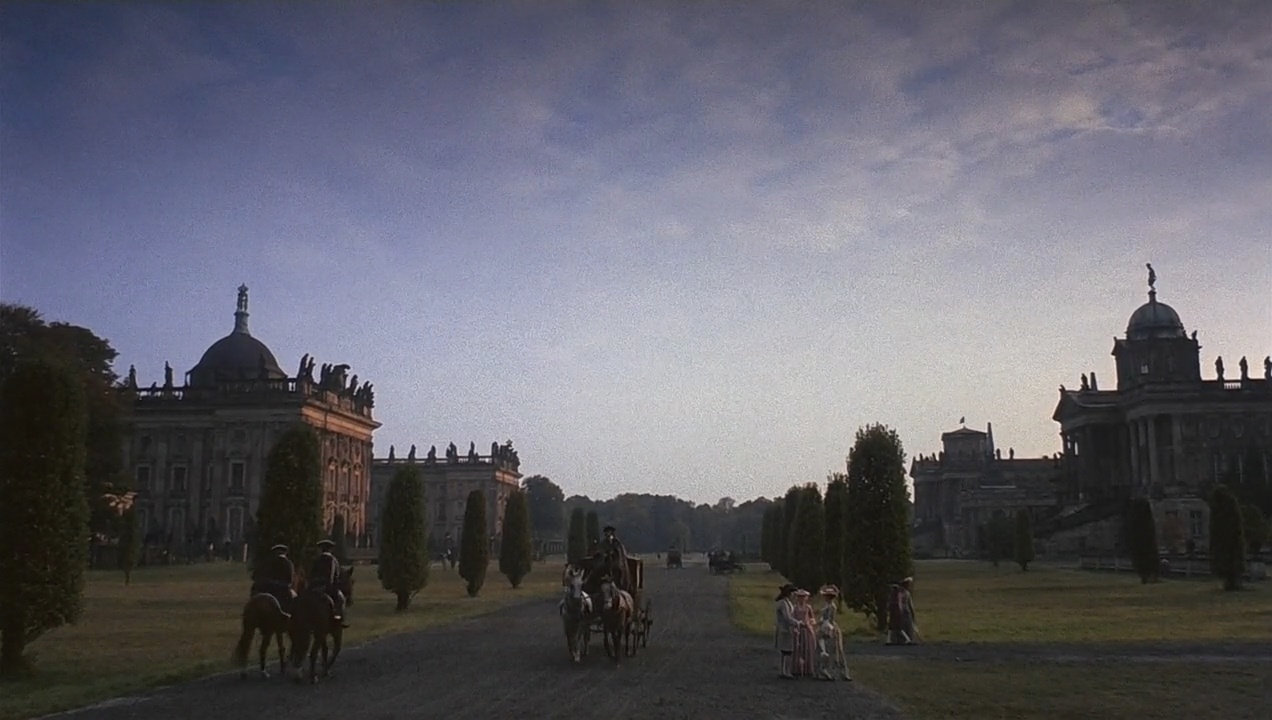

In 2001, we see how Kubrick finally uses space to make comprehensible what cannot be put into words with the surreal salon “beyond Jupiter”, where David Bowman’s transformation into the star child takes place. Kubrick himself said that it functions as a kind of zoo for Bowman to be observed in by alien beings – it is designed to make him feel at home, but based on a limited understanding of actual human surroundings. Kubrick contrasts the salon’s organic shapes with the artificial light that streams out of the floor, reversing the setting in the rotating space station seen earlier in the film and making the space seem as unnatural as it is eerie. The imperfectly imitated baroque furniture adds the familiarity and distance of tradition, places Bowman in aristocracy and distant hierarchies (recalling the Palaces from Paths of Glory), and finally anticipates his fast ageing, which frees him from all these references.

In this way, space narrates the context and causality of Bowman’s metamorphosis without plot, narrator or shot having to do the work – Kubrick lets us experience the mythology and metaphysics of the film without a detour through language.

Perspective

Kubrick is 27 when he shoots The Killing, with Lucien Ballard directing photography, 20 years his senior and famous for his later work with Sam Peckinpah; an experienced cameraman, a professional. Kubrick’s instructions are clear, but not always comprehensible: He orders a wide-angle 25mm lens for a style-defining tracking shot from the back to the front room of the conspiratorial flat. Ballard would have to lay the tracks so close to the set that lighting would become disproportionately difficult. So he takes a 50mm lens, moves the camera back and explains to Kubrick that this will give him the same framing. Kubrick is stunned, confronts Ballard with the alternative of following his ideas or leaving the shoot – and wins. The old hand Ballard won’t question any further decision made by the beginner Kubrick.

A trained photographer, often shown next to the camera, at the lens or behind the video monitor, Kubrick was fanatic of the shot. Its definition through lens geometry, position and perspective of the camera was the linchpin of his work on set. It is only because Kubrick insisted on using wide-angle lenses even in the most intimate shots in The Killing (repeated and intensified later in Eyes Wide Shut) that the situations captured are always slightly distorted, that they speak of a lurking paranoia.

The most famous example of Kubrick’s shot fanaticism, however, are the night-time interior scenes in Barry Lyndon: to be able to film them by candlelight without additional lighting, he had a Mitchell camera demolished in order to put the fastest lens ever made in front of it – a collaboration of Carl Zeiss and NASA, only two of them ever produced. (A funny footnote is the now widespread narrative that Kubrick staged the moon landing for NASA and the lens was his reward.)

The images resulting from Kubrick’s fanaticism are so extraordinarily clear and unambiguous that there is never any doubt about their artificiality. There is no threat of being overwhelmed by the setting, no illusion about our distance from what is happening. Kubrick’s gaze – and thus ours – is rational, not affective, structuring, not unifying; “scientific”, says Georg Seeßlen. This gaze does not replicate that of the participant (unless that is the relevant cognitive perspective), but orders events and objects for us as viewers: spatial boundaries are always positioned just inside the image boundaries, camera movements are tightly controlled, the spatial geometry just as clearly defined as the movements within it.

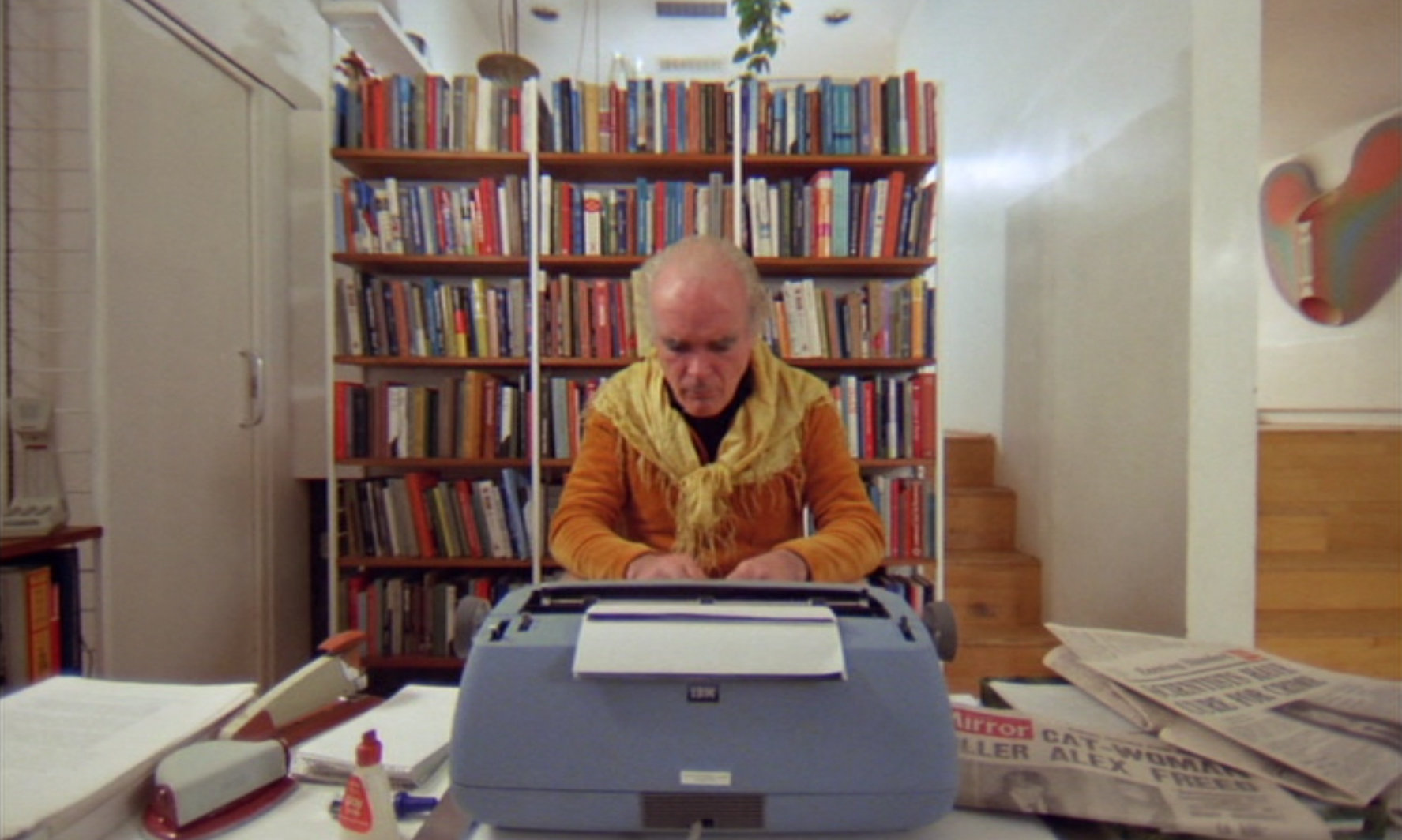

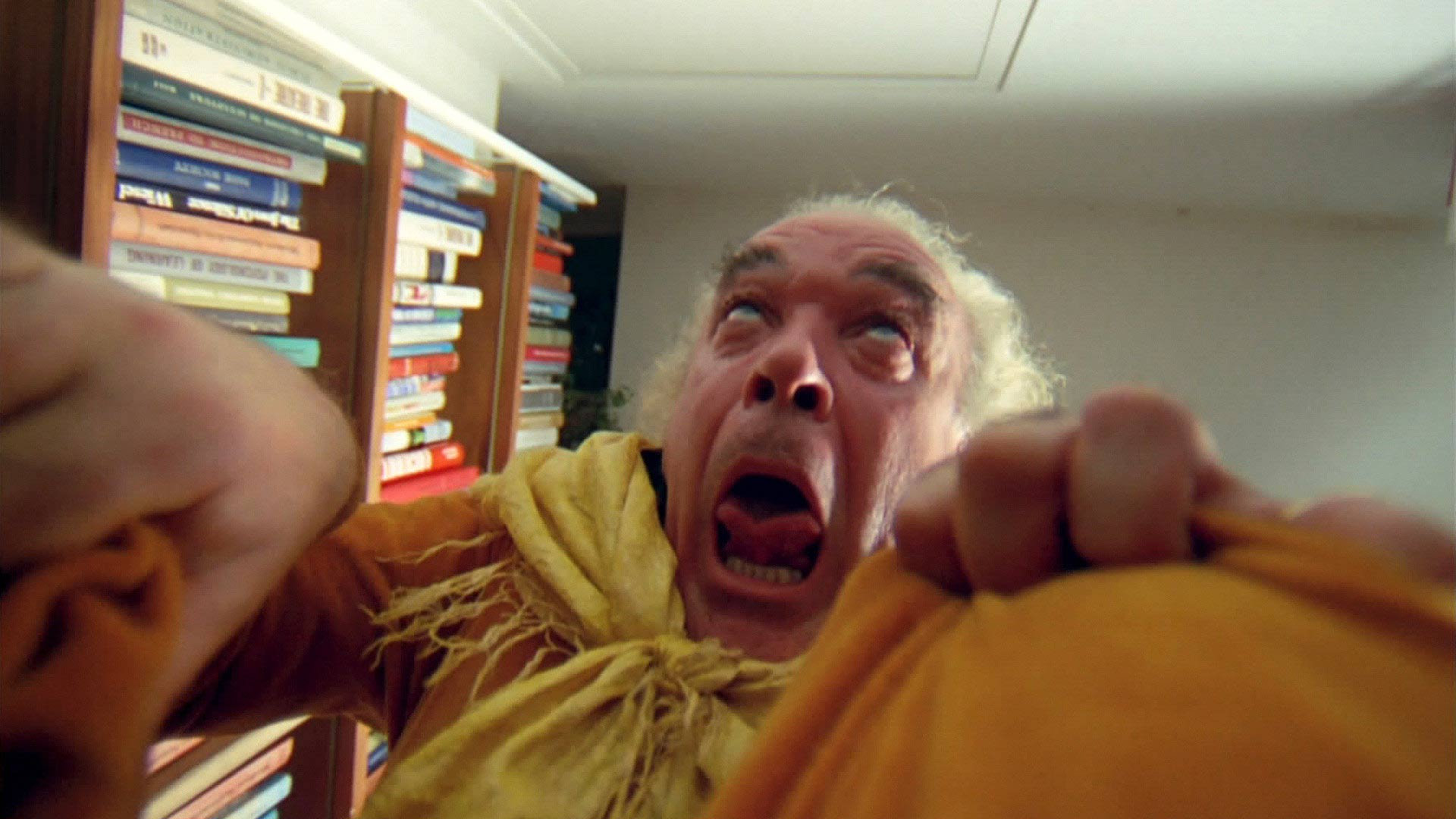

Case in point: two sequences from A Clockwork Orange, which incidentally quote and continue the journey from The Killing in terms of plot context and wide-angle optics: The identical parallel journeys from the writer Mr Alexander’s desk to his wife (and her space sofa) and his caretaker (and his weight-lifting bench), their way through the mirrored corridor to the door, and Alex’s two completely different appearances move as if “on cue”; the geometry of the camera movement divides the images and the rhythm of our perception, the differences between the scenes stand out all the more clearly because their structure is exactly the same. Architecture, interiors and actors are presented by the camera, not portrayed. In the end, this gaze turns Kubrick’s hyperreal spaces into “worlds so aestheticised, so overdetermined that their reality is dubious”, as Larry Gross says about Eyes Wide Shut.

With Dr. Strangelove, Kubrick had established his grammar of shots. Three perspectives dominate: the view from below into the corner of the room, whose movement is the panning of the camera from a fixed position; the view at the same height frontally into the room, which is moved as a parallel movement of the camera; and the handheld camera, which is used whenever things get real and we are supposed to share the perspective of the actor(s).

The view of the delusional General Ripper and how he defends his office in Dr. Strangelove, the tour of the Overlook Hotel at the end of the holiday season in The Shining, the fight scenes in Dr. Strangelove, A Clockwork Orange and Barry Lyndon are each typical examples of Kubrick’s three perspectives. They each give the captured scene its specific meaning: We realise Ripper’s madness not only from the dialogue, but from the way the camera is looking up to an imposing but cornered general; we experience the labyrinthian character and overwhelming power of the Overlook Hotel through long parallel camera journeys following our protagonists. The adoption of the actor’s perspective reaches its climax when Alex’s suicidal fall in A Clockwork Orange is shown from his own point of view, until the camera shatters on the floor (and literally breaks).

The level of consistency of these perspectives across all films might be astonishing, but it is precisely the unambiguity and regularity of Kubrick’s grammar that allows his films to speak on a level that is largely independent of plot and dialogue.

Just how far Kubrick takes the embodiment of a concept in a perspective can be seen in the juxtaposition of Barry Lyndon and The Shining: The former shows our (historical) distance from the story by making almost every shot a zoom out of or into an image that could be part of the 18th century canon (and thus reflects our view of the past as well as the pace of the time). The latter draws us in with the perspective that is created by the steadicam’s fluid movement into and through the space and lets us experience the labyrinthine character of the hotel ourselves.

But neither of these things overwhelm the viewer: they are wordless explanations of the film’s events we engage with because they are so incredibly tempting and so completely plausible, not because we have no other choice as e.g. in Spielberg’s case. And the more often we experience them, the better we know and recognise them, the more familiar we are with Kubrick’s grammar, the more willingly we accept these explanations. And the better we understand Kubrick’s films.

Montage

The early Kubrick, it is said, was above all other directors influenced by Max Ophüls and his long, smoothly moving shots. When he talks about montage, Kubrick does not refer to Sergei Eisenstein, but to Vsevolod Pudovkin: the cut should not connect sometimes disparate impressions for purposes of agitation and argumentation, but string together images “step by step”, each images being the “direct continuation of the others”, so that “each shot gives the incentive to transfer interest to the next”. Kubrick’s films should therefore be entirely organic.

But already The Killing demonstrates that they actually function completely differently: Anticipating Tarantino & Co, the film deliberately cuts up all temporal and causal structure and arranges the material in such a way that we have to reconstruct these connections ourselves, but the patterns and motifs behind them are expressed all the more clearly. This interplay between the involvement of the viewer and a complete formulation of the concept characterises all of Kubrick’s films and makes them, for both the recipient and the author, works that are, also in the montage, conceived, not felt. (How different from the great antipode Tarkovsky!)

On the one hand, this applies to the macrostructure of the films, whose story is always visibly and precisely divided into “non-submersible units”, such as Burpelson Air Force Base, War Room and B-52 bomber in Dr. Strangelove, “The Dawn of Man”, “18 Months Later” and “Jupiter and Beyond the Infinite” in 2001, or Parris Island, Da Nang and Hué in Full Metal Jacket. In addition, and similar to classical drama, they develop in clearly separated acts, usually four of them. In The Shining, for example, these are the way to the hotel, moving in and making a home, the way into madness, and climax and death.

On the other hand, the editing places the individual scenes in a rational, not an emotional relationship to each other: In Paths of Glory the cuts from Colonel Dax to the soldiers on his tour through the trenches as well as those from the labyrinth of the battlefield to the palace halls of the military leadership explain domination and hierarchy, contrasting realities of life whose incompatibility fuels the fundamental conflict of the film. Thoughts, not feelings, are conveyed.

The same is true of the cuts in Barry Lyndon, which act as a counterpoint to the long takes and zooms that dominate most of the film’s sequences: They do not support the comprehensibility of the emotions shown or increase the pace and thus the brisance of Barry’s rise and fall, but primarily heighten our awareness of the slow pace within the shots and thus of our conceptual as well as cultural distance from the events. The fact that this makes the film seem like a walk through a museum, as main actor Ryan O’Neal one said disapprovingly, is only testimony to this deliberately created distance, which for Kubrick is the only justified and authentic approach to a bygone era.

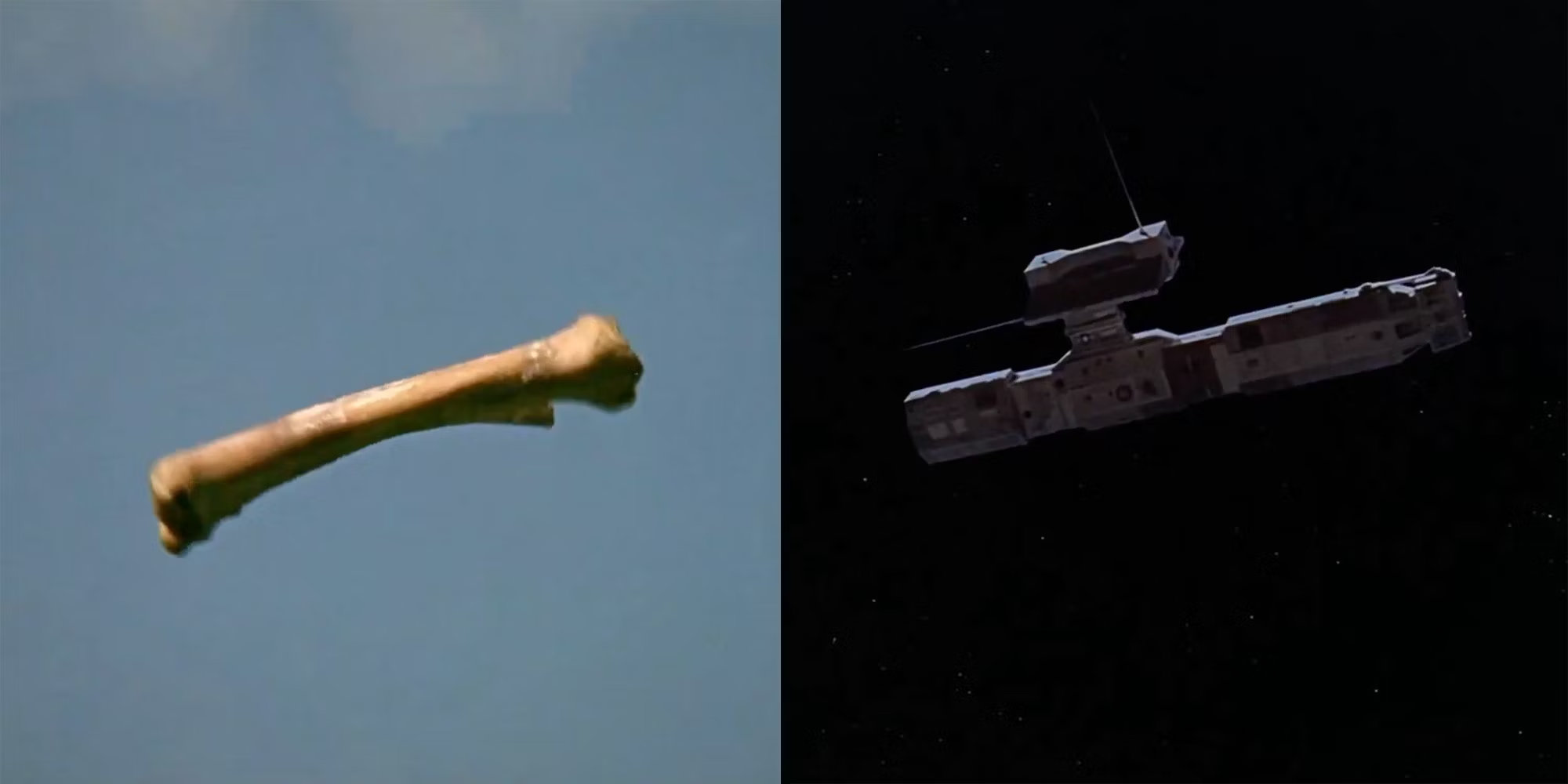

Finally, the probably most famous cut in film history, the match cut from a bone thrown into the air to a military spaceship in Earth orbit in 2001. It represents the essence of Kubrick’s intellectual montage. Not only does a single cut cover a temporal distance of three million years; at the same time, the matching of the two objects shows the continuity over this distance and the path that humanity has travelled: it has conquered space with tools designed for a struggle for power and supremacy that began millions of years ago. The cut expresses a general theme of the film, a theme that finds its culmination in the figure of HAL 9000 and the conflict between dehumanised humans and all-too-human machines.

The incorporation of the form and movement of the preceding shot into the following one thus doesn’t serve the organic continuation of a series of images, but is the condition and means of Kubrick’s argumentation in and with images. In this, it is closer to the “argumentative cut” of the late Eisenstein than to Pudovkin’s smooth montages.

Author and audience

Kubrick is often wrongly categorised as an auteur. What distinguishes

true auteur filmmakers like Hitchcock, Truffaut

or Scorsese

is the personal view, the autobiographical reference, the pervasive

subjectivity of their filmmaking. All this is missing in Kubrick. His

eagerly secured and preferably exclusive screenplay credits (“the auteur

syndrome” Terry

Southern, his co-author on Dr. Strangelove, called it) are

the only reference to the – in Umberto Eco’s words – empirical

author Kubrick.Eco (1990)

Scorsese’s origins and cinematic socialisation can be found in abundance in the themes and topoi of his films. Truffaut’s admiration of Hitchcock speaks from his entire oeuvre, and Hitchcock’s obsessions are essentially the material of his thrillers. Kubrick’s content and the form he gives it don’t reference anything personal. The author takes a back seat to the work. Kubrick’s refusal to comment on his films, his complete retreat into the private sphere fit perfectly into this picture.

The only thing that remains of the author Kubrick is his method,

which, in Eco’s framework, constitutes the model author.Ibid.

It makes the rational perspective and the theoretical

nature of Kubrick’s films possible in the first place. Kubrick’s films

speak to us with clarity and unambiguity because of his endless

perfectionism, the insistence on absolute control, the thinking through

and designing of all aspects. “The ideal way to make a film would be to

wrap up after every scene and go away for a month to think,” Kubrick is

reported to have said – and his way of working came very close to this

ideal.

The disappearance of Kubrick the empirical author also opens up new perspectives on the – notably un-filmic – off-screen narrator, which Kubrick uses in every film except 2001, The Shining and Eyes Wide Shut. The classic and certainly accurate justification is that a narrator frees setting and dialogue from delivering exposition or highlighting emotions. This allows camera and editing to concentrate on showing rather than explaining, and thus be pure film. At the same time, the narrator can add levels of meaning – e.g. establish complicity with the protagonist as in A Clockwork Orange or create suspense (instead of surprise) in Barry Lyndon. In Kubrick’s work, the off-screen narrator is always in service of the concrete film, not of an ideology of filmmaking.

From the point of view of the author stepping back behind his work, the additional narrative instance takes on further significance: by inserting an invisible, but identifiable voice, a further level of abstraction is created between the viewer and the author. The narration through shot and cut, which bears Kubrick’s signature, is relativised by the off-screen narration, further minimising the relationship to the empirical author. Kubrick makes himself invisible.

At the same time, however, the additional voice creates space for narrative incongruities – and with them possibly a glimpse of the empirical author, the human being Stanley Kubrick after all, even if he himself speaks of the “objective reality” shown in the pictures. In a film that is otherwise shown entirely from the perspective of his first-person narrator (A Clockwork Orange), it is striking that there are exactly two scenes that the “humble narrator” Alex cannot have experienced. That his victim and later patron Alexander is less a democrat than an aristocrat (“They have to be led!”); that he sees through Alex and, continuing to mimic the benevolent host, plots against him; how he exposes Alex and what he sets in motion against him – we see all this, although Alex can’t possibly witness it. This in turn opens up the possibility that this interpretation of events, the exposure of the liberal Alexander as just another scheming cheapjack play-actor, springs from Alex’s imagination and only serves his self-protection. The additional narrative instance thus creates space for a sceptical optimism that Kubrick is otherwise all too often denied.

While Kubrick the empirical author almost completely disappears behind the model author, the importance of the empirical reader can hardly be overestimated. For all of his consistency and control, few directors were more uncertain about the actual impact of his films than Kubrick. Alongside forced decisions (the lack of sex in Lolita) and omissions justified by film logic (the missing cake fight in Dr. Strangelove), radical re-cuts were sometimes made under the impression of audience reactions: After some audience members left the premiere of 2001 early, Kubrick removed 20 minutes of film – which is why, for example, the waltz of the Orion III approaching to the space station seems to miss a few steps. Kubrick cut the final sequence from The Shining after the first screening – and another 28 minutes for the European version of the film. The digital fig leaves in the orgy sequences of the US version of Eyes Wide Shut reportedly had his approval. And his first film, Fear and Desire, will probably never be seen again – Kubrick bought all existing copies and locked them away. No small price to pay for perfectionism.

Epilogue

Those who accuse Kubrick of coldness and cynicism may find confirmation by all the intellectuality and distance that characterise Kubrick’s films. In reality, however, they are the condition for an endeavour that speaks of a deep humanity: making films about the world and our place in it that look sceptically behind the myths and mechanisms of everyday life.

Of course it is easier to make films about how the world should be or how we feel in it. But such films are mostly either superficial or cathartic, serving primarily emotional needs in both cases. For Kubrick, on the other hand, films about our world and our place in it must deal rationally with its irrationality, reflect on the conditions of their knowledge production, and give an honest account of their positionality.

Thus if one doesn’t want to make superficial or cathartic films, but films geared towards learning and understanding, then the detached, examining, not the feeling gaze is a prerequisite for their truthfulness. To understand cinema as a place of thinking, not of feeling is a consequence from this that breaks with the tradition of conventional narrative cinema. Kubrick has drawn it radically like no other film maker. He was never indifferent to the fate of humanity and the fate of humans – he just continues to ask and think where others are satisfied with a sigh and/or a sob.

Kubrick said of Arthur Schnitzler in 1960: “It’s difficult to find any writer who understood the human soul more truly and who had a more profound insight into the way people think, act, and really are, and who also had a somewhat all-seeing point of view – sympathetic if somewhat cynical.”

Kubrick and his work could not be described any better.

Sources

- Ciment (2001): Kubrick: The Definitive Edition

- Eco (1990): The Limits of Interpretation

- Ginna (1960): “The Artist Speaks for Himself: Stanley Kubrick” (excerpts published in 1999)

- Hughes (2000): The Complete Kubrick

- Jung & Seeßlen (1999): Stanley Kubrick und seine Filme

- Kolker (2011): A Cinema of Loneliness (4th edition)

- Walker (2000): Stanley Kubrick, Director: A Visual Analysis (revised edition)

Acknowledgements

The stills from the films discussed in the essay are used for educational purposes, constituting a fair use of copyrighted material.

I am grateful to Michael Wopperer, Gregor Groß and the Motorhorst community for comments on earlier versions of this essay.